We return this week from our special, breaking-news post about the recent reappearance of our one-hit-wonder, Twitter-sensation, spectabulous Banner-tailed Kangaroo Rat. This T-Rex of Portal may not be here to stay, but we’re sure excited she stopped by. What is here to stay is that pesky plot switch we mentioned last month. We’re going to continue our series of Portal science updates and tell you all about that now:

REGIME SHIFTS AND A NEW FRONTIER AT PORTAL

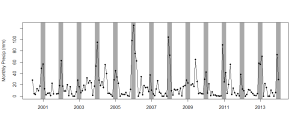

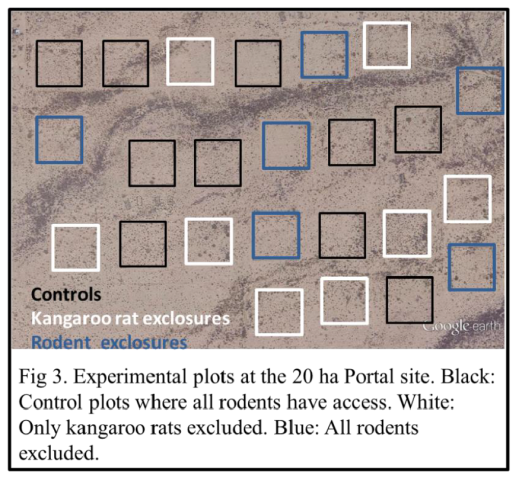

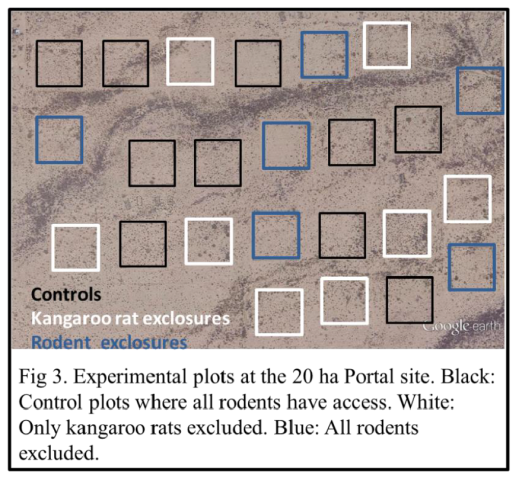

The last time we checked in at this blog prior to the 2015 plot switch, Erica was battling monsoon season to record desert rodent dynamics on the twenty-four long-term experimental plots that have been censused almost monthly since the site was established in 1977 by James Brown, James Reichman, and Diane Davidson. That’s thirty-nine years of tracking the occurrence of various species of small mammals. That’s over four hundred visits to Portal, AZ to trap, measure, weigh, and tag rats. And it all started before scientists had thought very much about why fluctuating species abundances in a community might be interesting.

This is cool because now we have decades of data (most of it publicly available) on how these scurrying, hopping, burrowing creatures have been interacting at Portal, just in time to see a surge of researcher interest in community ecology and species dynamics. For example, we were able to document an abundance of the small, pink flower Erodium cicutarium in plots where the competitive seed-foraging Kangaroo rats were excluded (Allington et al, 2013). And, after many years of pondering its absence, we recorded a resurgence of the Northern pygmy mouse, Baiomys taylori, a peculiar trend that would have gone undetected without regular sampling efforts. We’ve seen shrubs increase in both size and abundance, changing the entire look of those plots, not to mention the nature of the local foraging and shade resources. Ecology, in all its complexities, happens over long time scales. To understand it, we must record it over short ones. Few studies exist that have managed to do both, and we are excited about the scientific opportunities the history at Portal affords us and others who use our data.

Erodium cicutarium (left) has been increasing in abundance in plots where Kangaroo rats are excluded. Baiomys taylori (right), the Northern pygmy mouse, has resurged from apparent rarity.

So now that we have amassed this monstrous dataset and finally understand more about how these rodents have been faring, cohabiting, and influencing the plants of these twenty-four plots in long-term treatment groups over nearly forty years, naturally we decided to turn it all on its head. Yes, after over four hundred samples of the twenty-four plots in their original treatment states, we got a grant from the National Science Foundation to switch them all around. Why? Because we’re scientists, and we like to poke systems to see what happens.

Because we scientists often want to be useful in addition to curious, we also like to simulate real expected ecological change so that we can predict likely outcomes and plan for them. Our world is rapidly changing. We need to understand how ecological communities will respond. When we’re not watching and recording, or sometimes even when we are, seemingly small changes can add up to big shifts. A breeze, a little water vapor, a small temperature change can suddenly turn into a monstrous hurricane, for example, that introduces a whole new set of rules and challenges to human existence. Similarly, ecological systems can undergo extreme, abrupt changes in state that are very hard to understand and manage unless they have been tracked before, during, and after that transformation.

Questions surrounding the idea of regime shifts, described as dramatic changes in populations, communities, and ecosystems over short periods of time (Hare & Mantua, 2000), represent relatively new challenges in the field of ecology, ones that the Portal project may be uniquely situated to address. Understanding regime shifts, or how communities of rodents may suddenly shift in their relative species abundances or resource usage, at Portal may help us understand what to expect from other ecosystems undergoing unprecedented levels of environmental change. We’re not promising X-(woman)-like vanquishing of Hurricanes. We study rats, not wolverines after all. But this is important stuff.

While hurricanes are exceedingly rare in the Arizona desert, there are subtler forces at work which may cause shifts in our Portal rodent community. Knowledge of these forces may help us, and other scientists, understand similar sudden disruptions in unmonitored groups and ecosystems. It’s the scientists’ mutant superpower — studying one thing ‘over here’ can help us predict and manage another thing ‘over there’ which we may have actually never seen…except in our mind’s eye.

The figure below, from Dr. Ernest’s 2014 grant proposal, shows three scenarios in which ecosystems and drivers (e.g. climate, nutrient input, biotic interactions) can be related in ways that might represent system-disrupting regime shifts. Sudden shifts in drivers (e.g. hurricanes) could cause a corresponding shift in ecosystems (e.g. massive urban destruction), which would constitute a regime shift. The same ecosystem pattern, however, could be triggered by simply crossing a threshold along some seemingly innocuous linear increase of a driver (like a slowly rising sea level that causes the sudden collapse of a city when it finally submerges the business district, or the state of water as it’s gradually heated past its boiling point). Regime shifts, like the melting of sea ice caps, can be hard to undo. Sometimes an ecosystem can be brought back down from a boil by turning down the driver dial. But sometimes an ecosystem will fail to revert back to its original state after a driver has increased and then decreased again, taking the ecosystem along a new trajectory. At Portal, where neither massive urban destruction nor hurricanes are a major concern, this might come in the form a plant that fails to return to a location after a particularly dry summer even after rains have resumed, or a Banner-tail Kangaroo rat who once reigned mighty and may never be seen again.

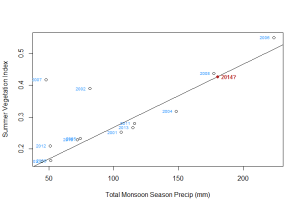

To poke the system and test this at Portal, in March 2015, we reversed some of the long-standing plot treatments. We also, of course, maintained some of the plots in their original treatments to serve as reference plots, against which we can test the existence and magnitude of potential regime shifts caused by introducing a large granivore as a driver. This has rarely been experimentally tested because few systems have the long-term data, ability to simultaneously cause a jump in an ecosystem driver in both directions, and enough plots to maintain replicates with reversed and reference plots.

The Portal project’s twenty-four plots and well-monitored, gated rodent communities is an ideal system to study regime shifts because it does not have these common experimental design limitations. Because we manipulate rodent access to plots via gates of different size, it is also shockingly easy to change the rodent community on a plot – we can make new gates by clipping holes in the fencing, remove gates by applying patches over them, or change the size of gates (and the species that can enter the plot) by either patching or clipping to create new hole sizes. So last spring, Dr. Morgan Ernest led the hardware-cloth-stripping-team in reassigning plots to their new experimental treatment, ending an era, but never the science:

Messing with the treatments

Erica securing the new hardware cloth pieces to close the old gates (left). This little guy (right) wishes we could strip the hardware cloth off him. But we are done with that task.

In a gesture of inclusiveness and diversity characteristic of the Weecology lab group ideology, we broke down barriers between different rodent communities by enlarging or creating gates in some of the plots that had previously excluded the granivorous, large-skulled (and adorable) Kangaroo rats:

A Kangaroo rat, Dipodomys merriami. What plot wouldn’t want these cuties?

But because this is science and not social revolution after all, we are also testing the influence of these large-skulled favorites as ecosystem drivers by excluding Kangaroo rats from some of their previous home plots by patching up or narrowing gates in plot fences that had previously allowed them to pass into these areas.

Example of a gate in a Control plot, open (left) and closed (right), which provides free, open access for all knowledge-(or seed)-seeking rodents!

Example of a gate in a Kangaroo rat exclosure plot, open (left) and closed (right), which is very oppressive of Krats, but great for controlling their influence in plots as a driver.

In case you have ever doubted the dedication of field biologists, thinking perhaps that we enjoy a life of sipping Coronas in a scenic field station after a day of wandering through the hills sniffing at plants, we would like to explain to you the unnatural nature of hardware cloth. Hardware cloth is not cloth. It is, however, hard. It is also pointy and sharp and vexingly narrow. To enact the plot treatments switch described above, the valiant hardware-cloth-team-of-2015 used pliers to strip countless thin layers of wire off of small metal squares of fencing, creating exposed, pointy wire ends along the hardware cloth, which must then be woven through the tiny squares in the existing plot fence to close off or narrow old treatment gates. They then cut or adjusted new treatment gates in the existing fence hardware cloth to create new access for the Kangaroo rat ‘drivers.’ Science is not all high-tech gadgets and sophisticated computer algorithms. Sometimes real science is stabbing yourself with hardware cloth one thousand times and squatting on the ground in the blazing hot desert to sew patches over gates in metal fences because you want to see what the rats will do. We happen to actually love this type of self-brutality in the name of science, and how it makes our evening Coronas, enjoyed together around the campfire at our beautiful field station, taste that much better.

The field crew taking a break at the Ramada, our two-sided field station.

And that is the story of how the plot switch, and the finger-massacre, of 2015 was recorded in Portal history. We won’t show you the blood, but we will show you the final plot map result, and a much cleaner schematic of plot treatment shifts:

Next time on the Portal blog we will fast-forward to a year after this historic plot switch when, wiser, hardier, and with more Band-Aids and guacamole in tow (though there is never, ever enough guacamole), the Weecology field crew hit the road again, in our new University of Florida vehicle, to undertake the 447th sampling of desert rodents, and the twelfth under a possible new regime.

Activist Yuri Kochiyama (Wikipedia.org) and people who look like their dogs (barkpost.com).

Activist Yuri Kochiyama (Wikipedia.org) and people who look like their dogs (barkpost.com). The Pied Piper, keeper of the rodent gates.

The Pied Piper, keeper of the rodent gates.