As part of our Portal 40th anniversary celebration, some of us will contribute our thoughts on our favorite species at Portal. We’ve already had several posts on the Banner-tailed Kangaroo Rat (a universally beloved species at the site). But, I have a confession, while I love Banner-tails, they are not my favorite species at Portal (cue collective gasp). No, my favorite species is the grasshopper mouse. We have two species of grasshopper mice at Portal, the Northern and the Southern Grasshopper Mouse (Onychomys leucogaster and Onychomys torridus).

They are similar in their biology and morphology. Both are small (usually less than 6 inches or 120-163 mm in length including the tail) and weigh less than 40 grams (or 0.088 lbs). Given their similarities, I like them equally well, so will simply refer to grasshopper mice generically for our purposes today.

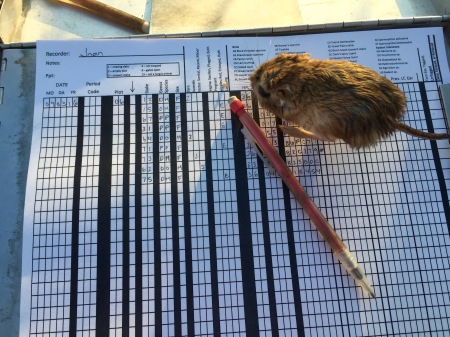

Anyone who has interacted with a grasshopper mouse probably remembers the encounter. Grasshopper mice have sharp little teeth and love to use them. Keeping an eye on the front end wouldn’t be that hard if you didn’t also have to also keep a sharp eye on the back end. The teeth are just a distraction from the fact they are trying to coat you with liquidy, yellowish diarrhea. Oh, and did I mention that grasshopper mice REEK. Yes, I do mean reek. Their oily, acrid scent curdles the nose hairs and lingers after the little rodent is gone (probably because they managed to smear some poo on you in retribution before they headed off).

So right about know, you’re probably wondering why this reeking, vicious little rodent is my favorite species at Portal (or you’re wondering what this says about my personality). With so many amazing rodents to choose from at Portal, what makes the grasshopper mouse so special? The reason grasshopper mice are notably more aggressive than our other species is that grasshopper mice are predators – yes, predators. They will eat seeds when resources get scarce and cache seeds in their burrows (Ruffer 1965), but they actively hunt insects, small rodents, arthropods, and even reptiles. They even hunt scorpions – see for yourself. The video below shows in sequence an adult, a subadult, and a juvenile attacking a scorpion. The adult knows to chew off the stinger quickly. The younger ones….well, it’s definitely a more difficult experience for them, though they eventually get their meal.

Why can these mice withstand scorpion stings? Without getting into sodium ion channel-level detail , basically they have a special protein that binds to the scorpion’s neurotoxin that changes how it works (Rowe and Rowe 2008)– as a result not only doesn’t the sting hurt, it actually ends up numbing the area of the sting (Rowe et al 2013).

Grasshopper mice also have surprising social relationships. There are a variety of reports that male and female grasshopper mice form strong pair-bonds and that both sexes participate equally in offspring care (McCarty and Southwick, 1977) and make the nest burrows together (Ruffer 1965). Grasshopper mice have a calling behavior using sounds that are almost ultra-sonic (Hafner and Hafner 1979). Though members of a family group have similar calls, every individual has unique call characteristics, which means that Grasshopper mice may be able to use these calls to communicate with family members over long distances (Hafner and Hafner 1979). When they call, they stand on their hind legs and throw their heads back:

Some mammalogists cannot see past the reeking, bitty little animal with the magical stinking poo that seems to get on you no matter how hard you try to avoid it. But when I see a grasshopper mouse, I see a little mouse who thinks it’s a coyote. I see some cool evolution at play that takes a normal mouse and turns it into a scorpion-resistant killing machine. I also see a brave little mouse fearlessly taking on a scary world. There’s something about it that just makes me smile. And then I go get some hand sanitizer.

Scientific Studies Cited in this Post:

Hafner, M.S., and D.J. Hafner. 1979. Vocalizations of Grasshopper Mice (Genus Onychomys). Journal of Mammalogy 60:85-94

McCarty, R., and C. H. Southwick. 1977. Patterns of parental care in two cricetid rodents, Onychomys torridus and Peromyscus leucopus. Animal Behaviour 25:945–948.

Rowe, A. H., and M. P. Rowe. 2008. Physiological resistance of grasshopper mice (Onychomys spp.) to Arizona bark scorpion (Centruroides exilicauda) venom. Toxicon 52:597–605.

Rowe, A. H., Y. Xiao, M. P. Rowe, T. R. Cummins, and H. H. Zakon. 2013. Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel in Grasshopper Mice Defends Against Bark Scorpion Toxin. Science 342:441–446.

Ruffer, D. G. 1965. Burrows and Burrowing Behavior of Onychomys leucogaster. Journal of Mammalogy 46:241–247.

All the site focused research (papers that use our data as the primary focus of their analysis) was done by or in collaboration with someone affiliated with the project. If other researchers are using our data, so far they tend to either use it as part of a meta-analysis (i.e. as one of many data points in the analysis) or to make a figure for their statistical or conceptual paper that has an empirical example of what they are talking about. (Three papers cite a Data Paper for reasons that defy classification. After reading their paper I have no idea why they cited us)! This number of citations listed by Google Scholar is probably a little lower than the database’s actual use in papers because data citations for meta-analyses often get shoved off into the supplementary materials and are not indexed by Google Scholar as a result. Our usage in meta-analyses is probably higher, but it is unlikely that we’ve missed a paper focused solely on data from our site.

All the site focused research (papers that use our data as the primary focus of their analysis) was done by or in collaboration with someone affiliated with the project. If other researchers are using our data, so far they tend to either use it as part of a meta-analysis (i.e. as one of many data points in the analysis) or to make a figure for their statistical or conceptual paper that has an empirical example of what they are talking about. (Three papers cite a Data Paper for reasons that defy classification. After reading their paper I have no idea why they cited us)! This number of citations listed by Google Scholar is probably a little lower than the database’s actual use in papers because data citations for meta-analyses often get shoved off into the supplementary materials and are not indexed by Google Scholar as a result. Our usage in meta-analyses is probably higher, but it is unlikely that we’ve missed a paper focused solely on data from our site.